UMass CTF 2020: Reverse Engineering Writeups

Introduction

This page details my reversing writeups for The University of Massachusetts Amherst CTF. This CTF was originally just an internal CTF but I knew one of the moderators Sam. Overall it was a great CTF and I really enjoyed it; they definitely had some unique challenges.

All my scripts and the provided files from the CTF can be found here.

Baby Crackme I

Prompt

I haven’t touched a computer since I retired. Can you help me decipher this program I wrote 30 years ago? …

You should be able to solve this one, even if you’ve never written C before; it isn’t essential to understand every single line. If you do want a quick (one page) reference on C, though, look here.

Created by @Jakob

Hint

Strings in C are arrays of characters.

TLDR;

The flag is declared in plaintext in the source file which is compared against the users input. You can pull it out yourself you have bash do the heavy lifting for you.

head -n38 crackme.c | tail -n +7 | cut -d "=" -f 2 | cut -d ')' -f 1 | tr -d "\n\r' "

Solution

Since the source code for this challenge is provide I just opened the file in a text editor.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int check_flag(const char *flag)

{

if (strlen(flag) != 32) { return 0; }

if (flag[0] != 'U') { return 0; }

if (flag[1] != 'M') { return 0; }

if (flag[2] != 'A') { return 0; }

if (flag[3] != 'S') { return 0; }

if (flag[4] != 'S') { return 0; }

if (flag[5] != '{') { return 0; }

if (flag[6] != 's') { return 0; }

if (flag[7] != 'o') { return 0; }

if (flag[8] != 'm') { return 0; }

if (flag[9] != '3') { return 0; }

if (flag[10] != 't') { return 0; }

if (flag[11] != '1') { return 0; }

if (flag[12] != 'm') { return 0; }

if (flag[13] != '3') { return 0; }

if (flag[14] != 's') { return 0; }

if (flag[15] != '_') { return 0; }

if (flag[16] != '1') { return 0; }

if (flag[17] != 't') { return 0; }

if (flag[18] != '_') { return 0; }

if (flag[19] != '1') { return 0; }

if (flag[20] != 's') { return 0; }

if (flag[21] != '_') { return 0; }

if (flag[22] != 't') { return 0; }

if (flag[23] != 'h') { return 0; }

if (flag[24] != '1') { return 0; }

if (flag[25] != 's') { return 0; }

if (flag[26] != '_') { return 0; }

if (flag[27] != '3') { return 0; }

if (flag[28] != '4') { return 0; }

if (flag[29] != 's') { return 0; }

if (flag[30] != 'y') { return 0; }

if (flag[31] != '}') { return 0; }

return 1;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char flag[64];

fgets(flag, sizeof(flag), stdin);

if (strchr(flag, '\n')) { *strchr(flag, '\n') = '\0'; }

if (check_flag(flag)) {

printf("License key accepted.\n");

} else {

printf("Try again.\n");

}

}

For anyone who understands C this code is pretty easy to understand.

For those who do not understand C they may not get what is going on.

In C, and most languages main is the function that is called “first” when the program is executed.

In the function declaration we can see main takes two arguments int argc and char **argv.

These are automatically passed by the operating system when the program is called.

argc is the number of command line arguments being passed while argv is a array of strings, in C strings are arrays of characters. You can also things of argv as the commands you pass via the command line.

For example running the following comand ./chall test 1 b. argc would equal 4 and argv would contain ['/home/user/Documents/chall', 'test', '1', 'b'].

Note: the first argument for argv is always the path of the running executable!

Once in main the program creates a buffer called flag. for a string of 64 characters.

Following this it gets input from stdin of 64 characters and stores it in flag.

After pulling the input from the user it removes any new lines in the string buffer.

Then the flag is passed to check_flag.

This function is where the “meat” of the problem is. Here we can see each value of the users input is compared against some hardcoded values. You COULD pull the flag out by hand, but I’ve been trying to practice my bash scripting so I decided to use bash to solve this challenge.

First we need to just get the lines relevent to use to do that we can use head and tail.

After that we need to pull out just the flag values which can be achieved with two calls to cut.

At this point the output is just the flag but its across multiple lines so we can use tr to remove the newline characters.

head -n38 crackme.c | tail -n +7 | cut -d "=" -f 2 | cut -d ')' -f 1 | tr -d "\n\r' "

Flag

UMASS{som3t1m3s_1t_1s_th1s_34sy}

Baby Crackme II

Prompt

… back then, compilers weren’t very good. I wrote this version, hoping it would be faster. Can you help me figure out what I chose for the “license key”? …

You might need to understand a little bit more C for this one, but I believe in you!

Created by @Jakob

Hint

Characters in C are just numbers. This is a useful mapping of numbers to letters.

TLDR;

Assembly is inlined to compare each character of the users input against hard coded values. This one is definitely a little more tedious to pull out by hand.

for word in $(grep -i CMP crackme.c | cut -d ',' -f2 | tail -n +2|cut -d ')' -f1); do printf "\x$(printf %x $word)"; done;

Solution

Like the prior challenge the source code is provided so I’ll just use a text editor to view this challenge.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdint.h>

int check_flag(const char *flag)

{

struct registers {

uint64_t rax;

uint64_t flags;

};

#define FLAG_EQUAL 1 << 1

#define MOV(dst, src) dst = (uint64_t) src

#define ADD(dst, src) dst += src

#define CMP(a, b) if (a == b) regs.flags |= FLAG_EQUAL;

#define JNE(label) if ((regs.flags & FLAG_EQUAL) == 0) goto label;

#define MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(dst, src) dst = *((uint8_t *) src)

if (strlen(flag) != 32) { return 0; }

struct registers regs;

regs.rax = 0;

regs.flags = 0;

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 0);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 85);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 1);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 77);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 2);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 65);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 3);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 83);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 4);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 83);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 5);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 123);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 6);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 118);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 7);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 49);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 8);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 114);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 9);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 55);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 10);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 117);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 11);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 52);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 12);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 108);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 13);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 95);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 14);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 109);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 15);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 52);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 16);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 99);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 17);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 104);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 18);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 49);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 19);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 110);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 20);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 51);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 21);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 53);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 22);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 95);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 23);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 52);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 24);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 114);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 25);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 51);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 26);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 95);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 27);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 99);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 28);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 48);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 29);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 48);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 30);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 108);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, 31);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, 125);

JNE(fail);

MOV(regs.rax, 1);

goto exit;

fail:

MOV(regs.rax, 0);

goto exit;

exit:

return regs.rax;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char flag[64];

fgets(flag, sizeof(flag), stdin);

if (strchr(flag, '\n')) { *strchr(flag, '\n') = '\0'; }

if (check_flag(flag)) {

printf("License key accepted.\n");

} else {

printf("Try again.\n");

}

}

This challenge is pretty similar to Crackme I, it may just not look like it at first. The reason behind that is because the author obfuscated the code slightly by using custom macros to achieve pseudo assembly. The assembly language level is primarily where binary reverse engineering is performed.

Luckily this function’s main is identical to the prior challenges.

The main difference here is the check_flag function.

As I said earlier the author utilizes custom macros to define assembly instructions.

There is essentially just one block that is repeated over and over.

MOV(regs.rax, flag);

ADD(regs.rax, #1);

MOVZX_DEREFERENCE_BYTE(regs.rax, regs.rax);

CMP(regs.rax, #2);

JNE(fail);

In this block we load the flags register and grab an address offset from it. Following that we pull the actual contents of the address in register. Finally we do a comparison against a hardcoded value. If the comparison fails we jump to the fail block, otherwise we keep going.

The only values that change in the block are #1 and #2. For each consecutive block #1 is incremented, this is acting as the array, or string index. The #2 value is being used as the hardcoded value that the character SHOULD equal. The #2 value is what we need for the flag!

Like the past challenge I used bash to solve this one, for this it makes a little bit more sense because you’d have to pull out the values by hand and convert them to ASCII which is a pain.

First lets pull away everything except the CMP statements as those contain the values we need.

This can be achieved with the grep command, unfortunately when CMP is defined it is pulled too so lets ignore that will tail.

After we pull out the CMP lines we need to pull out the value which can be achieved with cut like in the prior challenge.

Just like before we now have our “flag” except all the values are on separated lines and still in the decimal equivalent and not in its ASCII printable form.

So instead of deleting all the newlines this time we will iterate over each line and convert it to ASCII using printf

for word in $(grep -i CMP crackme.c | tail -n +2 | cut -d ',' -f2 | cut -d ')' -f1); do printf "\x$(printf %x $word)"; done;

Flag

UMASS{v1r7u4l_m4ch1n35_4r3_c00l}

Baby Crackme III

Prompt

… and I lost the source code to this one. But you’ve worked your magic for the past two, so I’m sure you can figure this one out?

Welcome to hard mode! You’re going to have to learn to disassemble a binary.

Computers actually can’t run C or Java without compiling it down to “machine code” first. “Assembly” is a set of phrases we associate with certain “instructions” in machine code so that we can read it.

There are plenty of disassemblers out there, but an easy way of spitting out the assembly code to the terminal is:

objdump -D -Mintel crackme

But you’re going to have to do some digging on your own :)

Maybe try looking up “reverse engineering linux binary”?

Created by @Jakob

Hint

Once you get the disassembly, this is very similar to Baby Crackme II.

TLDR;

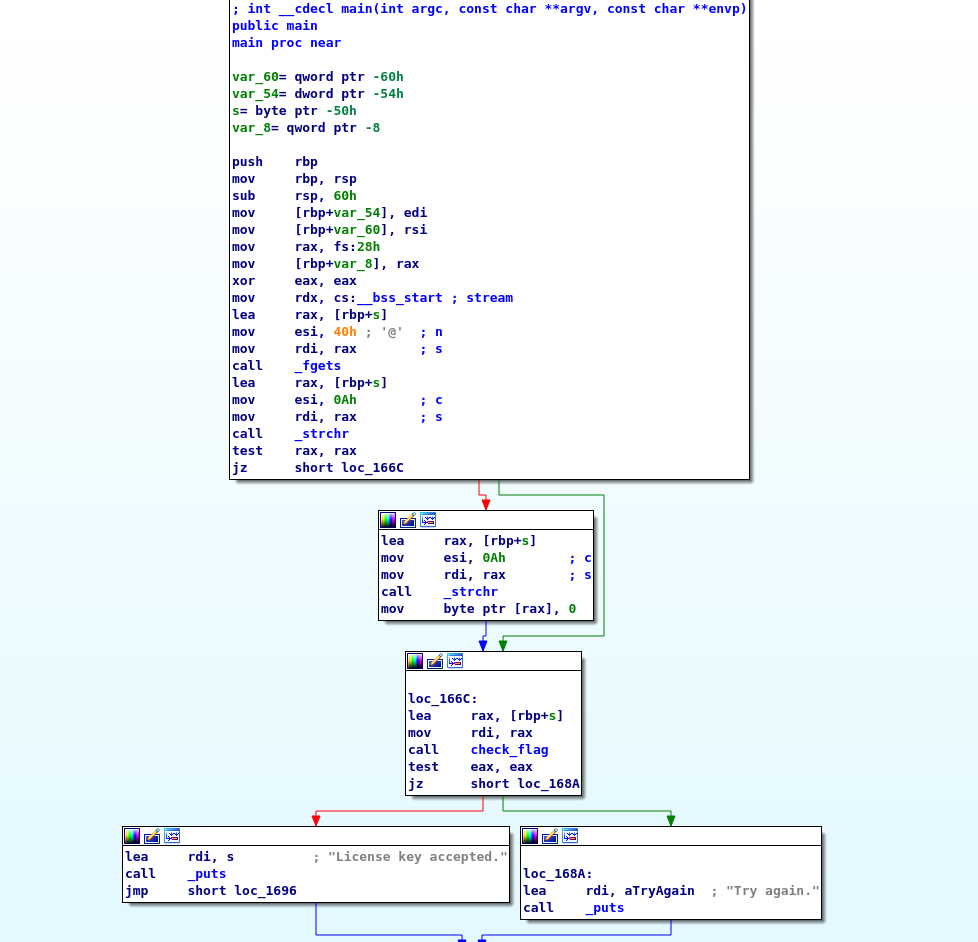

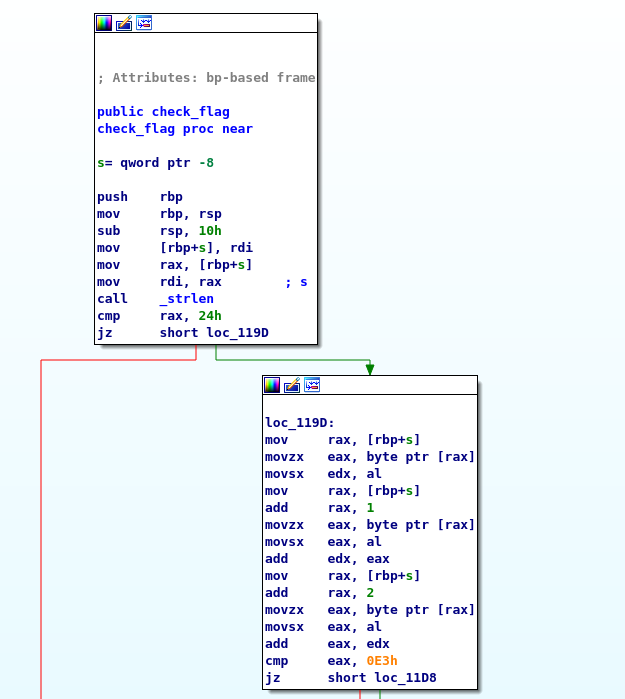

Loading the binary in IDA we see that it calls a check_flag function.

Inside of that function it works almost identically to the prior challenge.

We can use gdb to dump out the function and then the same script as before to get the flag!

gdb -batch -ex 'file crackme' -ex 'disassemble check_flag' | for word in $(grep -i CMP | cut -d ',' -f2 | tail -n +2|cut -d ')' -f1); do printf "\x$(printf %x $word)"; done;

Solution

For this challenge we are finally given a binary file instead of a source file. This means I won’t be able to just open it in a text editor and look at the source code, but instead will need to use a tool to disassemble the binary into assembly.

There are a bunch of good tools out there my favorites are either Ghidra or IDA. IDA has a nicer interface but it does not have as much features as Ghidra; in the free version that is.

Regardless, once the binary is opened in a disassembler the main function should pop up.

The main is pretty simple (it’s actually the same main we’ve seen before).

We can see a call to fgets to get the user input and after that the calls to strchr to remove the newline.

After those calls check_flag is called and based on its output we either get the good or bad message just like before.

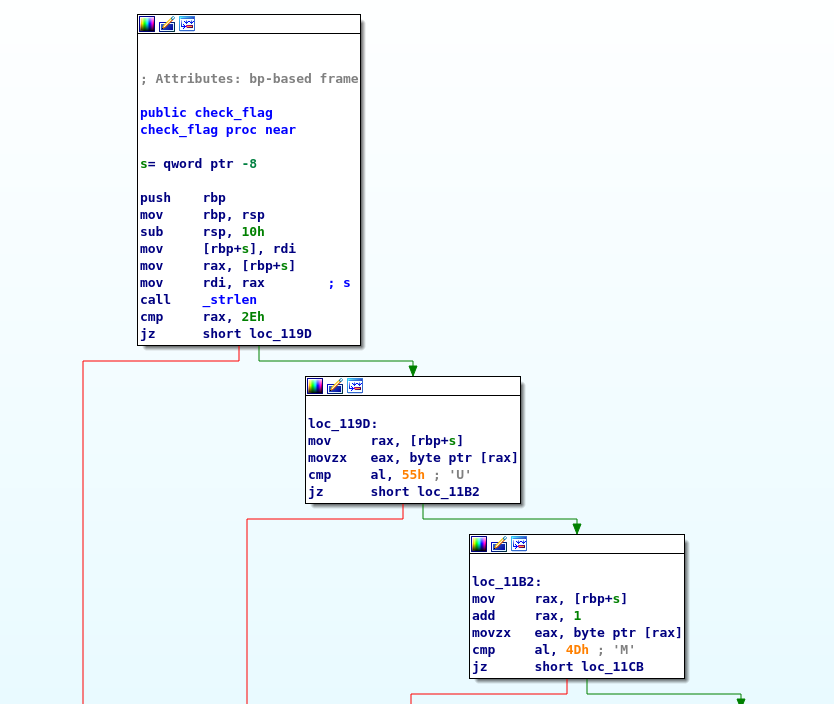

So just like before let’s check out check_flag.

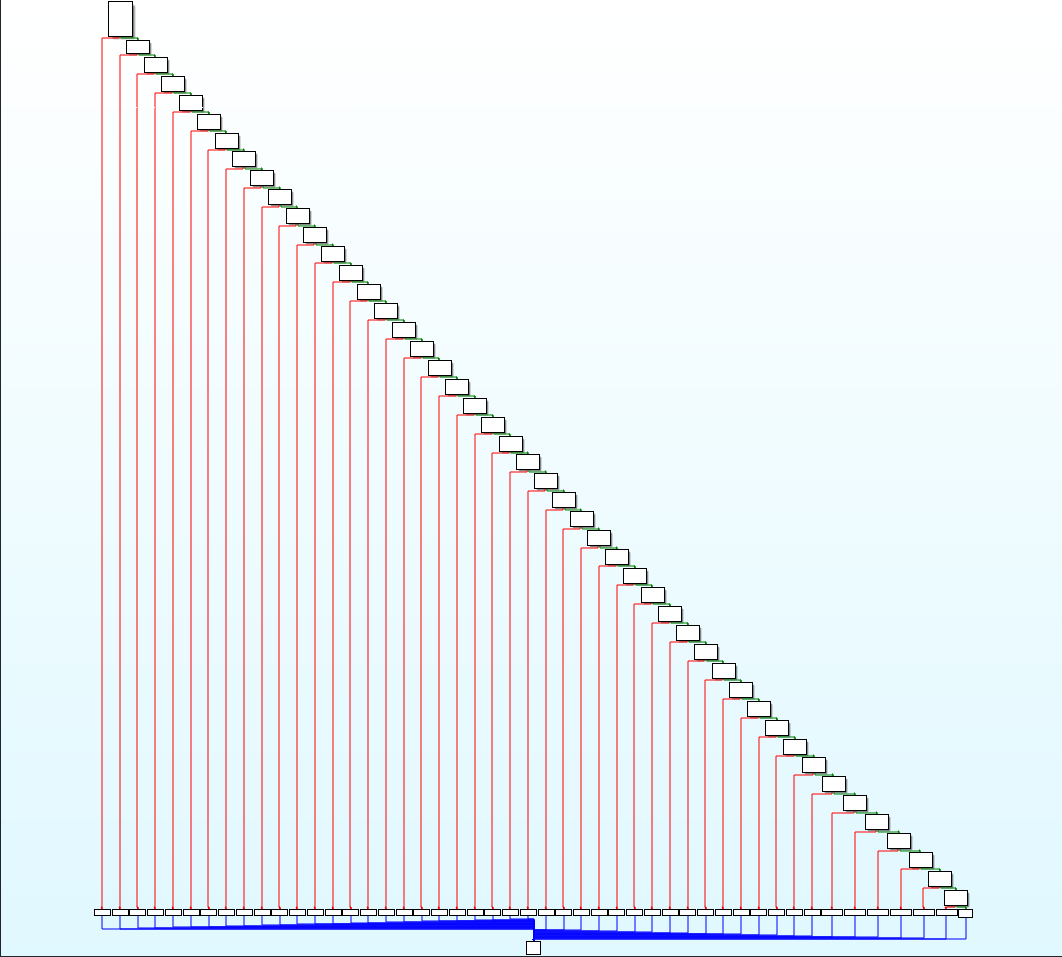

For someone not too familiar with reversing check_flag may look pretty complicated, but after you understand what is going on it isn’t really.

The first few lines checks the strings input to see if its the right length. If it is we keep going. Then we perform four lines of assembly; this should look very familiar. It is essentially the same commands we saw back in Crackme II! So just like I and II this function checks each value individually to see if it is the correct value and then returns 1 or 0 depending on if it failed or not.

Like before we can pull this out manully or use some scripting to achieve our goal, I chose the later.

We can actually use the same script as last time, however we just need to provide it with the disassembly as we don’t have it this time in a file.

To do that we can use gdb, or the GNU Debugger [which every reverse engineer (that does stuff on Linux) should be familiar with], to dump the check_flag function.

gdb -batch -ex 'file crackme' -ex 'disassemble check_flag' | for word in $(grep -i CMP | cut -d ',' -f2 | tail -n +2|cut -d ')' -f1); do printf "\x$(printf %x $word)"; done;

Flag

UMASS{now_you_c4n_put_4ss3mbly_on_your_r3sum3}

Linear Algebra

Prompt

Meh. I never understood why they make the CS students take MATH 235.

You’re going to have to disassemble this one, too. Sorry :)

Created by @Jakob

Hint

I’d go about this by writing down the equalities that are being checked in terms of symbolic variables (i.e. α + β + γ = 277), figuring out where the equations overlap, and then using the math skills I learned in high school.

TLDR;

Throw it at ANGR

import os

import angr

PATH = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), "crackme")

def main():

proj = angr.Project(PATH, auto_load_libs=False)

simulation = proj.factory.simgr()

constraint = lambda s: b"License key accepted" in s.posix.dumps(1)

simulation.explore(find=constraint)

if simulation.found:

pprint(simulation.one_found)

def pprint(solutions):

str_solutions = solutions.posix.dumps(0).replace(

b'\x00', b'\n').decode('utf8', errors='ignore').strip().split('\n')

for solution in str_solutions:

print(f"Flag found: {solution}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Solution

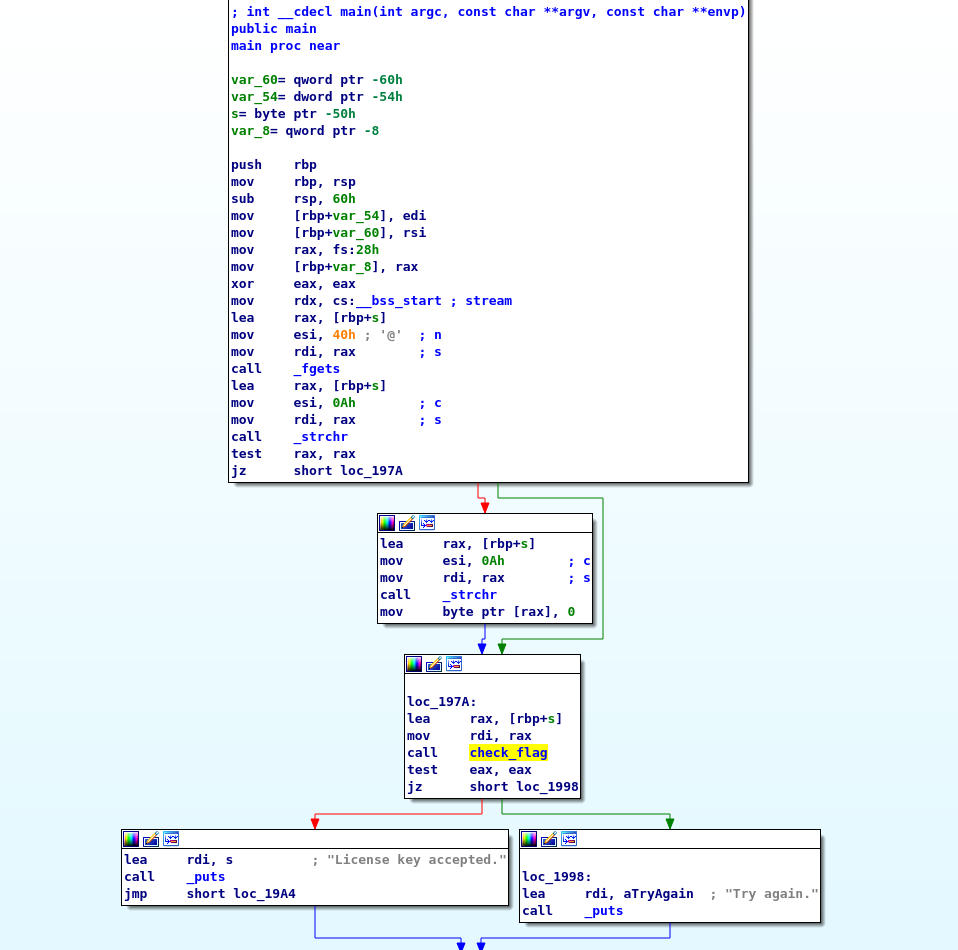

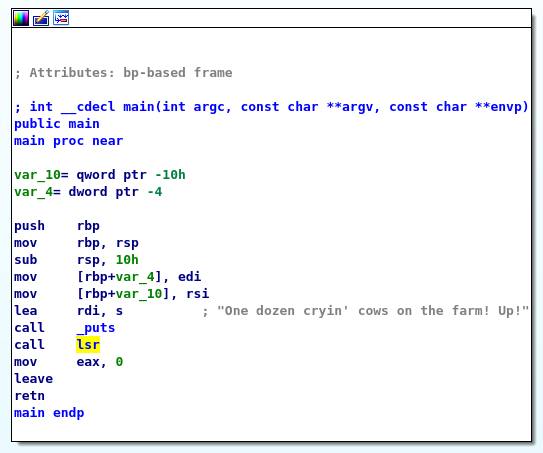

Like Crackme III we are provided with a binary for this challenge so load it up in your favorite disassembler.

Once in main we can see its still the same ole thing, so let’s go ahead to check_flag.

check_flag is pretty much the same this time but I really do not wanna do the math to figure out the flag so I’m gonna let a robot do it.

For this challenge I used ANGR a symbolic execution framework.

Symbolic execution tools purpose, or at least one of their purposes, is to find all the paths of a program.

Therefore we can use this to get us our flag!

ANGR abstracts away a lot of things for you which makes it easier to write quick scripts.

import os

import angr

PATH = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), "crackme")

def main():

proj = angr.Project(PATH, auto_load_libs=False)

simulation = proj.factory.simgr()

constraint = lambda s: b"License key accepted" in s.posix.dumps(1)

simulation.explore(find=constraint)

if simulation.found:

pprint(simulation.one_found)

def pprint(solutions):

""" Helper that prints the solution in a more human readable format

simulation - angr simulation object that represents the state the program is in

"""

str_solutions = solutions.posix.dumps(0).replace(

b'\x00', b'\n').decode('utf8', errors='ignore').strip().split('\n')

for solution in str_solutions:

print(f"Flag found: {solution}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

In main we first setup our environment with creating proj and simulation.

After that we create our constraint or what we want ANGR to solve for.

In this case we are looking for License key accepted being found in the output (standard output is the file descriptor 1 for *NIX Systems).

We then pass this constraint to explore and ask our simulation object if anything is found.

If there is a solution we then print it with pprint.

Fun fact: you can actually use the exact same script for Crackme III since the output we are looking for is the same. The only change that needs to be made is the filename in the PATH variable.

Flag

UMASS{c0mpu73r_5c13nc3_15_ju57_m47h}

Even/Odd

Prompt

I made this program that generates the flag and writes it to the console. It’s really fast!

Created by @Jakob

Hint

It isn’t “really fast”. This is an “optimize me” challenge. There are a couple of ways to go about this, but the easier routes involve “binary patching”. That’s the keyword you should be looking for online.

TLDR;

Patch the binary to calculate if an number is even / odd in a more optimized manner.

At address 0x11BD modify the next 8 bytes from

0x48 0x8b 0x45 0xE8 0x48 0x89 0x45 0xF8 0xeb 0x1c to

0x48 0x89 0xF8 0x48 0x83 0xE0 0x01 0x90 0xeb 0x41

mov rax, rdi

and rax, 1

nop

jmp short locret_1208

Solution

Let’s open this binary up.

Its main is pretty bare bones.

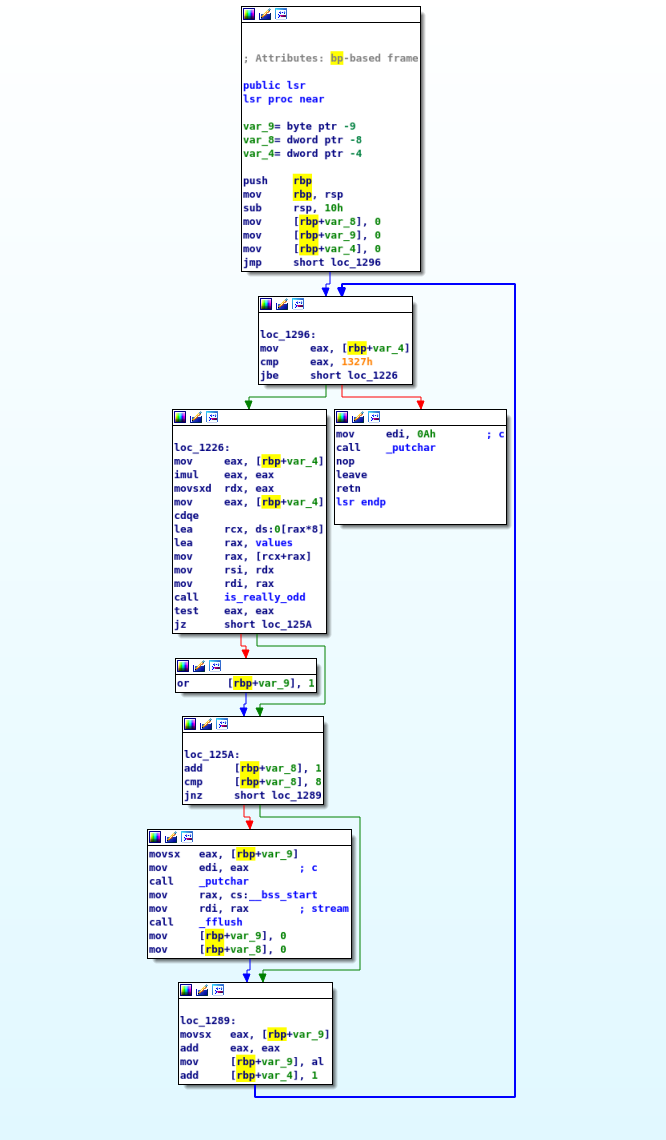

First a string is dumped and then lsr is called; lsr it is.

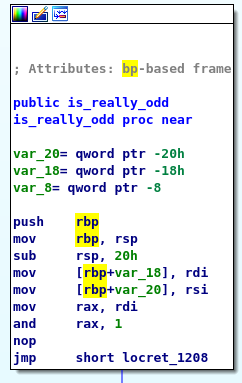

lsr is a tad bit more complicated.

We initalize some variables (rbp-8, rbp-9, rbp-4) to 0.

Following that we check rbp-4 against a hardcoded value 0x1327 and if we are less than or equal to it we jump, otherwise we leave this function.

It is safe to assume rbp-4 is the loop index value.

After that we do some “maths” to the value at rbp-4 and use the resulting value to pull a value from value a hardcoded array.

At this point do not be to worried about that math stuff that is going on.

All we care about is that based on the index value we perform some calculations and pull a value from values based on the result.

This new value along with a partial result from the math calculates is passed to is_really_odd.

Based on the return from is_really_odd we either perform an or operation or keep going.

Following that we check to see if rbp-8 is 8 if it is we will print a character to the screen.

We can assume that the flag will get printed to the screen.

Following the print rbp-8 is set to 0 and rbp-9 is set to the contents of eax and the loop index is incremented.

At this point there is a lot going on in this function and it seems pretty complicated especially since we are only looking at this statically and not dynamically.

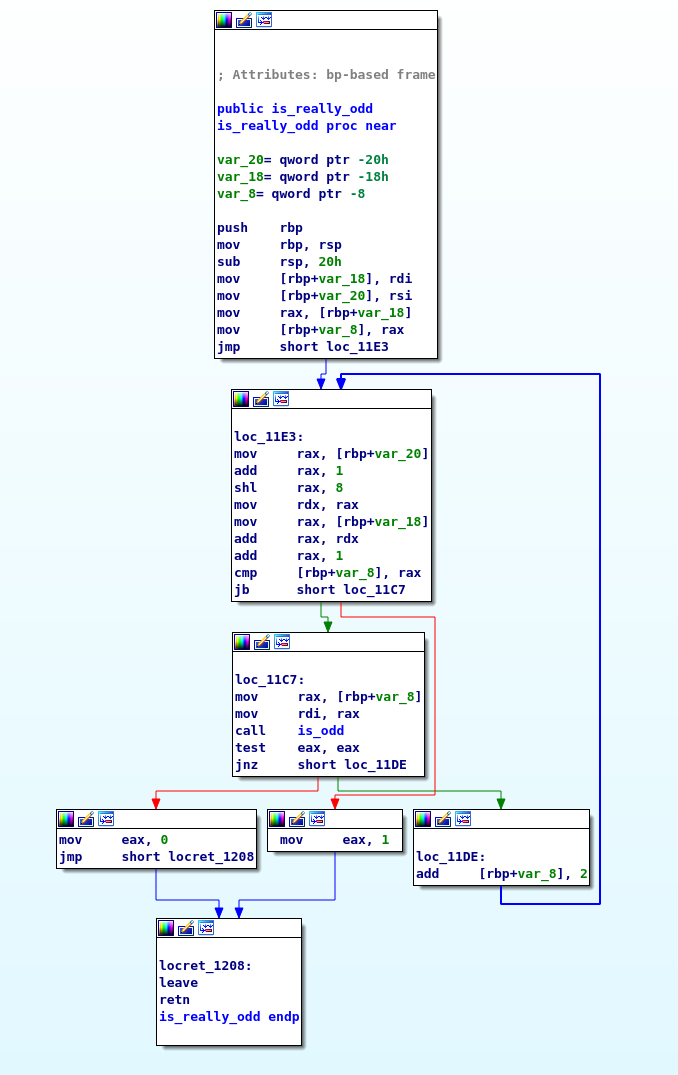

Before trying to debug this lets look into is_really_odd, especially since the name of the challeneg is Even/Odd.

In even we seem to loop and perform some math eventually calling is_odd and either returning 0 or 1.

At this point I am assuming if it is odd 1 is returned otherwise 0 is returned.

Let’s look into is_odd.

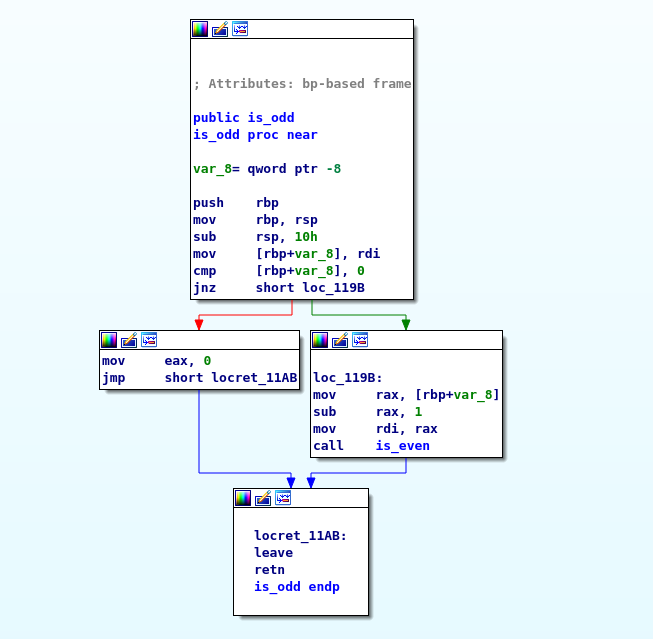

Here we see the input is compared against 0 if it is 0 we return 0 otherwise we subtract the input by 1 and call is_even with it. Alright… let’s look into is_even

Hmm.. okay so the same code except it calls is_odd and this returns 1 if the value is 0.

So essentially this code will recursively call is_even / is_odd until one reaches 0 and whoever reaches zero determines if a function is even or odd; this makes sense but it is not really efficient.

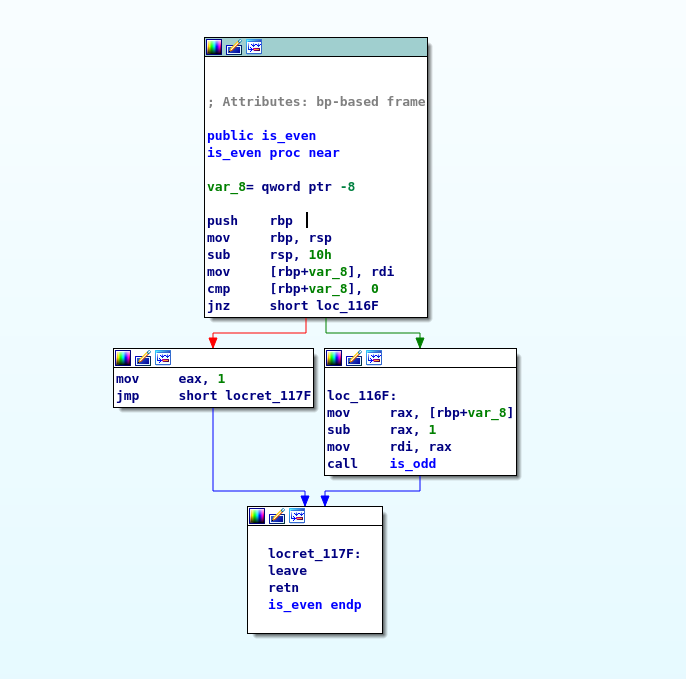

Let’s go back to is_really_odd and try to see if we can patch this program to be more efficient.

As far as I understand the value in RSI is just used to speed up the calculations by shrinking the input value a little bit.

I’m not entirely sure as I didn’t really look much into it as it looks like all we really care about is if RSI is even or odd.

For us to see if an number is even or odd all you have to do is AND it against 1.

If it is even it will return 0 and if it is odd it will return 1; so lets do that.

By patching out lines 6, 7, and 8 we can modify this program to better calculate even odds.

Out of all the reversing challenges I have to say this one was probably my favorite because it was fairly unique.

Flag

UMASS{w0w_y0ur3_p4713n7}

Marius

Prompt

I wanted to do my 575 homework in LaTeX, so I asked him what he used for editing. He sent me this.

TLDR;

The elisp script takes in a 30 long character string. Discards the first 6 characters and the last character.

It then swaps characters through out the string and compares the final manged string against a hardcoded one 1v_ms14__ks1rtpk_1dd13s.

Solution

For this challenge we are given an .el file which stands for Emacs Lisp.

Since this is just a source file we can open it in a text editor.

Unfortunately it doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Turns out the alias check-key is elips byte code so it will need to be disassembled before we can figure out what to do.

(defalias 'check-key #[(key) "\303\304!rq\210\305\216 c\210eb\210\306 G\307U\205F\310\311!\210\312\210\313u\210\310\314!\210\315 \210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\316\312!\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\316\312!\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\316\312!\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\316\312!\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\316\312!\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\316\312!\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\312u\210\316\312!\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\313u\210\316\312!\210\315 \210\317\320\321\306 \"\n\232)+\207" [#1=#:temp-buffer key toast generate-new-buffer " *temp*" #[nil "\301!\205

(define-derived-mode pro-mode prog-mode "Professional Mode"

"Major mode for professional Emacs users."

:group 'pro

(let ((key (read-from-minibuffer "Enter license key: ")))

(unless (check-key key)

(message "Key verification failed. Falling back to fundamental-mode.")

(fundamental-mode))))

(provide 'pro-mode)

I have never messed with Emacs before but thankfully the author gave a hint on how to load the file.

- Open GNU Emacs:

- Press Alt+X

- Type “load-file” and hit enter

- Type in “pro-mode.el” and hit enter

- To run pro-mode

- Press Alt-X

- Type in “pro-mode” and press enter

- To disassemble an elisp function

- Press Alt-X

- Type in “disassemble” and press enter

- Type the name of the function and press enter

Elisp disassembly is strange in that almost every operation pushes something to the stack. One can read about the disassembly here

If we run the instructions and disassemble check-key we get a dump of the disassembly of the function.

Which starts with defining a buffer.

byte code for check-key:

args: (key)

0 constant generate-new-buffer

1 constant " *temp*"

2 call 1

3 varbind temp-buffer

4 save-current-buffer

5 varref temp-buffer

6 set-buffer

7 discard

8 constant <compiled-function>

args: nil

0 constant buffer-name

1 varref temp-buffer

2 call 1

3 goto-if-nil-else-pop 1

6 constant kill-buffer

7 varref temp-buffer

8 call 1

9:1 return

9 unwind-protect

Following this we set the key, the users input, to the current buffer

10 varref key

11 insert

12 discard

13 point-min

14 goto-char

15 discard

16 constant buffer-string

17 call 0

After we setup the buffer we compare the length of the key against 30. If it isnt 30 we quit.

18 length

19 constant 30

20 eqlsign

21 goto-if-nil-else-pop 1

Now we delete the first six characters of the key; removes UMASS{

24 constant delete-char

25 constant 6

26 call 1

27 discard

After that the function deletes the last character of the key; removes }

28 constant nil

29 end-of-line

30 discard

31 constant -1

32 forward-char

33 discard

34 constant delete-char

35 constant 1

36 call 1

37 discard

Now we begin the encryption. First we move back to the beginning of the line.

38 constant beginning-of-line

39 call 0

40 discard

After that we move forward 10 characters and swap the character at the 10th location with the 11th location (counting as if the characters start at 1).

41 constant nil

42 forward-char

43 discard

44 constant nil

45 forward-char

46 discard

47 constant nil

48 forward-char

49 discard

50 constant nil

51 forward-char

52 discard

53 constant nil

54 forward-char

55 discard

56 constant nil

57 forward-char

58 discard

59 constant nil

60 forward-char

61 discard

62 constant nil

63 forward-char

64 discard

65 constant nil

66 forward-char

67 discard

68 constant nil

69 forward-char

70 discard

71 constant transpose-chars

72 constant nil

73 call 1

74 discard

Afterwards we walk back 10 characters, not the swap moves us forward a character so after this we will be at the second character.

75 constant -1

76 forward-char

77 discard

78 constant -1

79 forward-char

80 discard

81 constant -1

82 forward-char

83 discard

84 constant -1

85 forward-char

86 discard

87 constant -1

88 forward-char

89 discard

90 constant -1

91 forward-char

92 discard

93 constant -1

94 forward-char

95 discard

96 constant -1

97 forward-char

98 discard

99 constant -1

100 forward-char

101 discard

102 constant -1

103 forward-char

104 discard

We then swap character 2 and 3

105 constant transpose-chars

106 constant nil

107 call 1

108 discard

This loops four times so we can build a little Python script to solve this for us.

s = '1v_ms14__ks1rtpk_1dd13s'

for x in range(4):

tmp = s[9+i]

s[9+i] = s[10+i]

s[10+i] = tmp

tmp = s[0+i]

s[0+i] = s[1+i]

s[1+i] = tmp

i += 1

Flag

UMASS{v1m_1s_4_skr1pt_k1dd13s}